Jelena Krneta

William Blake – New age mistical poet

Who was the William Blake – the poet of hymn Jerusalem

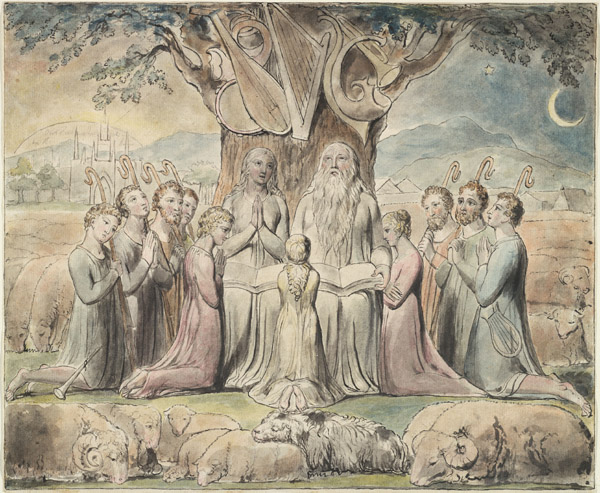

William Blake (November 28, 1757 – August 12, 1827) was an English poet, painter and print maker.He was born at London into a middle-class family. He was from earliest youth a seer of visions and a dreamer of dreams, seeing „Ezekiel sitting under a green bough“, and „a tree full of angels at Peckham“, and such he remained to the end of his days.

William Blake (November 28, 1757 – August 12, 1827) was an English poet, painter and print maker.He was born at London into a middle-class family. He was from earliest youth a seer of visions and a dreamer of dreams, seeing „Ezekiel sitting under a green bough“, and „a tree full of angels at Peckham“, and such he remained to the end of his days.

His teeming imagination sought expression both in verse and in drawing. At ten years old, he began engraving copies of drawings of Greek antiquities, a practice that was then preferred toreal-life drawing. Four years later he became apprenticed to an engraver, James Basire. After two years Basire sent him to copy art from the Gothic architecture churches in London. At the age of twenty-one Blake finished his apprenticeship and set up as a professional engraver.In 1779, he became a student at the Royal Academy, where he rebelled against what here garded as the unfinished style of fashionable painters such as Rubens. He preferred the Classical exactness of Michelangelo and Raphael.

In July, 1780, he was at the head of a rampaging mob that stormed Newgate Prison in London. The mob were wearing blue cockades (ribbons) on their caps, to symbolise solidarity with the insurrection in the American colonies. This disturbance, later known as the Gordon riots, provoked a flurry of paranoid legislation from the government of George III, as well as the creation of the first police force. Blake’s first collection of poems „Poetical Sketches“ was published circa 1783. After his fathers death, William and brother Robert opened a print shop in 1784 and began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson. At Johnson’s house he met some of the leading intellectual dissidents of the time in England, including Joseph Priestley, scientist; Richard Price, philosopher; John Henry Fuseli, painter whom he became friends with; Mary Wollstonecraft, feminist; and Thomas Paine, American revolutionary.

Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the American and French revolution and wore a red liberty cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror in the French revolution. Mary Wollstonecraft became a close friend, and Blake illustrated her „Original Stories from Real Life“. They shared similar views on sexual equality and the institution of marriage. In the „Visions of the Daughters of Albion“ in 1793 Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the right of women to complete self-fulfillment.

In 1788, at the age of thirty-one, Blake began to experiment with relief etching, which was the method used to produce most of his books of poems. Blake’s marriage to Catherine remained a close and devoted one until his death. There were early problems, however, such as Catherine’s illiteracy and the couple’s failure to produce children. At one point, in accordance with the beliefs of the Swedenborgian Society, Blake suggested bringing in a concubine. Catherine was distressed at the idea, and he dropped it. Later in life, the pair seem to have settled down, and their apparent domestic harmony in middle age is better documented than their early difficulties.

Later in his life Blake sold a great number of works, particularly his Bible illustrations, to Thomas Butts, a patron who saw Blake more as a friend in need than an artist. Geoffrey Keynes, a biographer, described Butts as ‘a dumb admirer of genius, which he could see but not quite understand.’ Dumb or not, we have him to thank for eliciting and preserving so many works.

About 1800 Blake moved to a cottage at Felpham in Sussex (now West Sussex) to takeup a job illustrating the works of William Hayley, a mediocre poet. It was in this cottage that Blake wrote Milton: a Poem (which was published later between 1804 and 1808). The preface to this book included the poem „And did those feet in ancient time“, which Blake decided to discard for later editions. This is ironic, because as the words to the hymn „Jerusalem“, this is now one of Blake’s most well-known if not well-understood poems. Slavery was abhorred by Blake, who believed in racial and sexual equality, with several of his poems and paintings expressing a notion of universal humanity: „As all men a realike (tho’ infinitely various)“. He retained an active interest in social and political events for all his life, but was often forced to resorting to cloaking social idealism and political statements in protestant mystical allegory.

His constant vision for humanity was rebuilding „Jerusalem“ on earth, a uniting of the physical and spiritual sides of human nature, free of economic exploitation, with people able to develop the full potential of their being. Blake rejected all forms of imposed authority, indeed was charged with assault and uttering seditious and treasonable expressions against the King in 1803, but was cleared in the Chichester assizes of the charges. Blake returned to London in 1802 and began to write and illustrate „Jerusalem“ (1804-1820).

He was introduced by George Cumberland to a young artist named John Linnell. Through Linnell he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients. This group shared Blake’s rejection of modern trends and his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. Blake benefited from this group technically, by sharing in their advances in water colour painting, and personally, by finding a receptive audience for his ideas.At the age of sixty-five Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job. These works were later admired by John Ruskin, who compared Blake favourable to Rembrandt.

William Blake died in 1827 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Bunhill Fields, London. In recent years, a proper memorial was erected for him and his wife. Blake is also recognized as a Saint in Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.

. . .

The art and poetry of William Blake is exquisite, but apart of being the artist and the poets was visionary above all. That includes being thinker, spiritualist, mystic and modern prophet. His work was absolutely exceptional concerning the time and historical background in which it had been created, but as well as concerning our contemporary perspective.

He had been creating in a period of transition in the European history, in the times of revolutions and when romanticism had been replacing neoclassicism. Although he is usually considered as the artist of romanticism, he never really and completely belonged to any historical art movement, nor his art could have ever been fully defined or interpreted. He always remained independent by creating and describing his own Universe, but also the Universe we are all living in, but never really experiencing it as he did, as the absolute and infinite. He was always completely devoted only to his inner guide – the Imagination in his creative process, so he was considered a rebel and even a madman by his contemporaries.

He was deeply spiritual, but never really traditionally religious. He created his own mythology and characters and his art is fully symbolic. Sources of his inspiration, apart of his vision and imagination, are various. It is known that he had been delighted and influenced by medieval art, and most of his art are illuminated books (illuminated manuscripts were very known and spreaded form of medieval art and painting) that so successfully combined his poetry and painting, even though his technique and expressionare original and very unique. His motives and representations often seem to be monumental, almost comparable with some of great mannirist wall decorations (of Michelangelo and Gulio Romano), but yet they are just book illuminations, which make his art even greater.

Unfotunatelly, his art was not understood, excepted or praised during his lifetime. Most of his life he had spent poorly and in isolation, but yet happy and fullfilled by his freedom and creativity, because glory ment nothing to him.

He was a genious, artist and visionary in its wholeness!

. . .

It is here that we begin to see the real Blake – or try to find out who the real Blake was. It is known that Blake felt that most of his art – whether poems or paintings – were merely representations of what he saw or knew in that other world. For example, Blake is credited with inventing a specific type of printing, but according to Blake, it was his brother Robert, following his death, who came to Blake in the night and explained to him the method of illuminated printing that he was to make his own.

Most of Blake’s paintings (such as „The Ancient of Days“) are actually prints made from copper plates,which he etched in this method. He and his wife coloured these prints with water colors. Thus each print is itself a unique work of art. As to his poems, some have seen these as automatic writing, dictated by beings from the other world, and written down by Blake, the scribe. Biographer Mark Schorer even states that Blake “went as far in the direction of the automatic as it is possible to go and remain poetry”.

The central question, of course, is whether it was real – or imagined… though for Blake the latter was real too. Hence, perhaps we should ask whether it was real or a hallucination, a mental aberration. Some, in his own time, have said that he suffered from hallucinations, others that he was just mad. William Wordsworth wrote: „There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott.“

None of the scenes in Blake’s art show landscapes as we know it. All his backgrounds are “eternal”, like darkness, or stars. Blake the painter does not do shepherds in a landscape or baby Jesus. Instead, he tackles subjects such as “the ghost of a flea”, or a portrait of Newton. “Ghost of a Flea” was the result of his vision of a flea and its statement that human souls sometimes resided in fleas, as a punishment for past lives. One friend was there when Blake had a second vision of the flea, at which point he would sketch him in more detail: “here he is – reach me my things – I shall keep my eye on him. There he comes! His eager tongue whisking out of his mouth, a cup in his hands to hold blood and covered with scaly skin of gold and green.”

Again, for Blake, seeing such ghosts was not at all upsetting; it was but one in a series of supernatural visitors, including, apparently Satan – the true devil – “all else are apocryphal”.

Late in life, Crabb Robinson had a conversation with Blake, in which heasked: “You use the same word as Socrates used. What resemblance do you suppose is there between your spirit and the spirit of Socrates?” Blake answered: “The same as between our countenances. I was Socrates… a sort of brother. I must have had conversations with him. So I had with Jesus Christ. I have an obscure recollection of having been with both of them.”

Indeed, it was Blake himself who said „I can look at the knot in a piece of wood until it frightens me.”

Despite using Christian imagery repeatedly, Blake was a mystical prophet, not a biblical prophet. He saw the Bible as a very long poem. For Blake, a more genuine bible were the writings of Emmanuel Swedenborg. Blake’s friends nevertheless said he did not see himself as his disciple, but more like a fellow visionary.

But Blake had to – and did – use Christian imagery. „The Marriage of Heaven“ and Hell is one of his books, a series of texts written in imitation of biblical books of prophecy, but expressing Blake’s own intensely personal Romantic and revolutionary beliefs. The book describes the poet’s visit to Hell, a device adopted by Blake from Dante’s Inferno and Milton’s Paradise Lost. As several others of his works, „The Marriage of Heaven and Hell“ revealed the mysticism of Swedenborg. Newton is probably his most famous painting, in which the physicist is cast in the role of the Great Architect of the Universe – revealing a strong influence of Freemasonry.

Foreshadowing Dali, who would claim to be the first painter of the world of quantum physics, Blake seems to have been the first painter of the world of physics. But his mind was definitely quantum physical, if not even more modern. He is centuries ahead of Rupert Sheldrake when Blake writes that “Matter, as wise logicians say, cannot without a form subsist, and form, say I, as well as they, must fail if matter brings no grist.” Did he reject Newton and the scientific approach?

In life, Blake did not object to reason, but did not submit to its authority, seeing it merely as the agent of a partial truth. Indeed,speaking on consciousness – which he labelled Imagination – he stated that it was not subject to matter, echoed in one of his other famous sayings „If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

So what would death be like for a man who felt death did not exist?

At six o’clock in the evening on August 12, 1827, after promising his wife that he would be with her always, Blake died. Gilchrist reports that a female lodger in the same house, present at his expiration, said, „I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel.“ George Richmond gives the following account of Blake’s death in a letter to Samuel Palmer: “He died … in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that Country he had all His life wished to see & expressed Himself Happy.”

After his death, his wife Catherine continued selling his works. In fact, his first book, „Poetical Sketches“ (1783) was the only one published conventionally during his life. She said that her husband would appear daily to her, sit for some hours with her and advice her on how to run the business. It was no different than Blake’s relationship had been with his dead brother, whom, Blake stated, appeared to him often for a period of many years after his death. Hence, it seems, Blake was true to himself when he stated that „The imagination is not a State: it is the Human existence itself.“

Blake considered memory to be an aspect of time, and hence what Christianity labelled the “Fallen World”. For him, “Salvation” were imaginary states, where he could transcend time, to look upon “our ancient days before this Earth appeared in its vegetated mortality to my mortal vegetated Eyes. ”Despite having known the leading lights of his time, Blake’s fame would be post mortem. Still, in life, he had said that “I should be sorry if I had an earthly fame for whatever natural glory a man has is so much detracted from his spiritual glory. I wish to do nothing for profit. I wish to live for art. I want nothing whatever. I am quite happy.”

In life, Blake claimed that Milton had appeared to him several times. Others have stated that he had gone as far as to think that he was a reincarnation of Milton. Either way, his poem Milton is often seen as his achievement of the state of mystical union, his “spiritualglory”, with the remainder of his work, Jerusalem, the illustrations for the „Book of Job“ and „Dante“, as the retention of it. But just like Mozart left his Requiem unfinished, so did Blake die before completing his illustrations of Dante’s Inferno – the voyage into death. The commission for „Dante’s Inferno“ came to Blake in 1826, but his death in 1827 meant that only a handful of the water colours were completed. For Blake, it would not have mattered. He had, it seems, achieved his personal ambition in life and completed his spiritual quest. What had he learned? “These states exist now. Man passes on, but states remain for ever; he passes through them like a traveler who may as well suppose that the places he has passed through exist no more, as a Man may suppose that the states he has passed through exist no more. Everything is eternal.”

He added: “This world of imagination is the world of eternity… There exist in that eternal world the permanent realities of everything which we see reflected in this vegetable glass of nature.” Hence, Milton had died, but he still existed; so did Jesus; so did – would – Blake. As above, so below. As before, so after. As in life, so in death. There was only Eternity, in a grain of sand, a knot, or a flower, his paintings, or poems, or in Blake himself.

. . .

[…] Viljem Blejk se rodio 1757, upravo one godine za koju je Svedenborg tvrdio da je godina Strašnog Suda na nebu, od skromnih ljudi – oca Džejmsa i majke Katarine. „Vrata percepcije” su mu se otvorila još kao malome: 1765. godine ugledao je „drvo prekriveno anđelima”, zbog čega ga je otac, misleći da laže, hteo da pretuče, ali ga je majka izbavila. Imao je vizije „sahrane jedne vile”, ugledao „poroka Jezekilja”, „bog” mu se javio kroz prozor i naterao ga da zavrišti. 1767. godine počeo je da uči slikarstvo. […]